Gustaf Skördeman, nato nel 1965 a Nederkalix, è un autore, regista, sceneggiatore e produttore cinematografico svedese.

Skördeman è stato attivo anche come creatore di fumetti, pubblicando la fanzine Steve Stainless dal 1981 al 1990.

È apparso anche in Stockholm Live.

Dopo un’esperienza di 25 anni nel settore cinematografico, realizza finalmente il suo vecchio sogno e diventa scrittore.

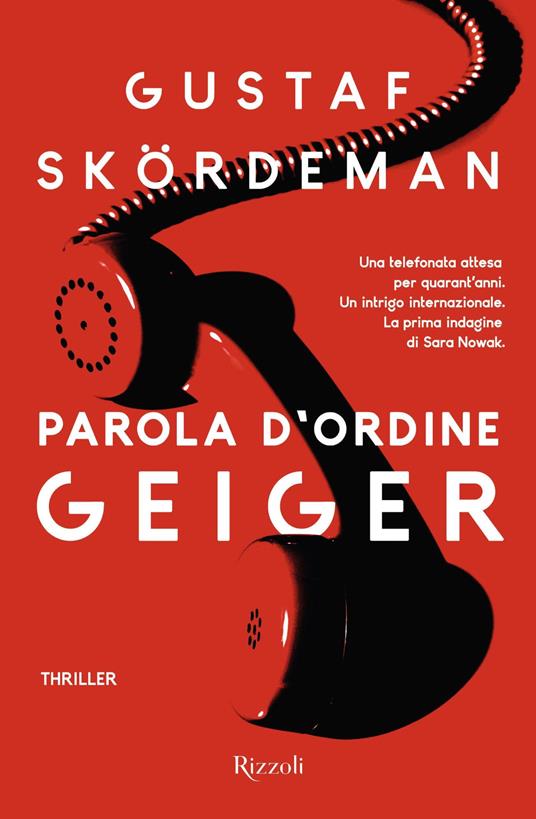

Le prime storie avevano un’impronta umoristica, ma il successo è arrivato con il suo primo romanzo spy-thriller, “Parola d’ordine Geiger”, titolo a cui ha lavorato per oltre dieci anni, pubblicato in Svezia nel 2020, proprio quando colpisce la pandemia.

Il successo è immediato, il libro viene tradotto in più di 20 paesi, i diritti cinematografici sono stati accaparrati e si reclama subito un seguito, infatti nel 2021 arriva Faust enel marzo 2022, la terza parte su Sara Nowak, Wagner.

Forte dell’esperienza come sceneggiatore, Skördeman sa esattamente quali corde andare toccare e confeziona una storia che ha tutta l’aria di essere terribilmente vera.

La storia del recente passato europeo e le vicende attuali s’incrociano in un susseguirsi di intrighi internazionali dal dirompente potere visivo, ma la cifra stilistica di questo autore si esprime nel potente sottostato umano che rende la protagonista, Sara Nowak, una figura profonda, tormentata, stupendamente vera come non se ne leggeva da tempo. Qui la recensione del libro.

Gustaf Skördeman ha gentilmente accettato di rispondere ad alcune nostre domande.

In questi giorni siamo alle prese con una crisi internazionale che sembra aver riportato il mondo indietro di almeno trent’anni. Ogni giorno si parla di rischio nucleare, cortine di ferro, spionaggio, tutti temi presenti nel suo romanzo, Parola d’ordine Geiger. Questo significa che la storia non muore mai veramente e che, nonostante questo, imparare dal passato è ancora impossibile?

Uno dei temi centrali di Geiger e delle parti successive è che la guerra fredda non è mai finita, che ci sono vecchie spie inserite nelle nostre società occidentali pronte a eseguire gli ordini dei leader russi, e che gli uomini al potere in Russia sono tutti vecchi uomini del KGB con la stessa visione del mondo di allora, e sono pronti a scatenare il caos in Europa, come si è tragicamente dimostrato dopo la pubblicazione di Geiger. Non abbiamo imparato dal passato, ma dobbiamo iniziare a farlo. La lotta per la democrazia non è mai finita, è un processo costante.

È evidente la scelta narrativa che hai adottato di non raccontare il mondo delle spie in stile Mission Impossible, proprio per rimanere in contatto con il tuo lavoro al cinema e in televisione. Il tuo romanzo ricorda piuttosto quei grandi affreschi di John Le Carré e la qualità della trama sembra quasi il risultato di un’esperienza diretta con quella realtà. Ha avuto accesso a testimonianze dirette?

Sono cresciuto durante la guerra fredda, nel nord della Svezia, dove c’erano molte zone militari e si parlava continuamente di spie e della minaccia di un’invasione da parte dell’Unione Sovietica. I miei genitori erano molto attivi politicamente nell’estrema sinistra, per cui il nostro telefono veniva messo sotto controllo dai servizi di sicurezza e il datore di lavoro di mio padre veniva avvertito del suo impegno politico. I miei genitori avevano anche amicizie personali con alcuni dei più noti terroristi o combattenti per la libertà palestinesi (a seconda della vostra visione del mondo). Solo durante le ricerche per i miei libri mi sono reso conto di quanto fossero legati tra loro queste persone che ho conosciuto da bambino e che hanno frequentato campi di addestramento in Medio Oriente. Inoltre, ho letto quasi un centinaio di libri per Geiger e ho ascoltato decine di interviste a vecchi attivisti e collaboratori.

Sara Nowak è una donna forte, una poliziotta intransigente ma anche una persona fragile, soprattutto nella vita privata. È una madre spaventata dal mondo verso il quale i suoi figli sono destinati ad andare con il passaggio all’età adulta, ed è anche una moglie insicura, forse perché troppo condizionata dalla sua professione. Pensi che questo sia un ritratto accurato della donna contemporanea?

È più incline a ricorrere alla violenza rispetto alla media delle donne, ma credo che condivida le preoccupazioni per i figli e per il loro futuro con la maggior parte delle donne di oggi, anche quelle che sono forti e capaci in altri campi. La maggior parte di noi vuole che i propri figli crescano forti e indipendenti, ma credo che molti genitori oggi si preoccupino di aver fatto abbastanza per preparare la propria prole alla vita. Il mondo di oggi è così complesso. Nel suo lavoro Sara ha visto molti dei lati più oscuri dell’umanità. Non c’è da stupirsi che sia preoccupata.

Un elemento ricorrente nel libro è la critica all’universo maschile. Ti consideri un femminista? Pensi che l’uomo abbia fallito nel suo ruolo di costruttore della società?

Se un femminista è una persona che crede nella parità di diritti tra uomini e donne (e tutti i non-binari), io sono sicuramente un femminista. Trovo sconvolgente che tanti traffici e violenze domestiche restino impuniti. E continua ad andare avanti. In effetti, le nostre società non si preoccupano di tutte queste tragedie e vite rovinate, e credo che la ragione sia in gran parte che i sistemi giudiziari sono dominati da uomini conservatori di mezza età o più anziani.

Un tema centrale del romanzo è la posizione geopolitica della Svezia, quasi una sorta di crocevia delle trame internazionali ordite dalle superpotenze, le stesse che oggi sembrano dirigersi inesorabilmente verso un nuovo conflitto. È questo che rende il suo Paese l’ambientazione ideale per un thriller come questo?

La posizione della Svezia e il fatto che siamo stati neutrali per 200 anni, almeno ufficialmente, hanno reso la Svezia un ottimo terreno di incontro per le spie per molto tempo. Sia durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale che durante la Guerra Fredda era un luogo perfetto per incontrarsi, poiché si poteva arrivare qui abbastanza facilmente da diverse parti e incontrarsi in condizioni di sicurezza. Penso anche che l’ingenuità svedese sia stata di grande aiuto per quelle spie e cospiratori. Per lo stesso motivo, negli anni Settanta la Svezia era un luogo popolare per i terroristi provenienti da diverse parti del mondo. Venivano dal Sud America, dal Giappone, dal Medio Oriente, dall’Italia e dalla Germania Ovest per incontrarsi e organizzare la cooperazione.

Ciò che colpisce di Geiger è il suo stretto legame con la realtà, nonostante il libro sia stato pubblicato in Svezia due anni fa (mentre in Italia è appena arrivato). Crede che già da tempo ci fossero segnali di ciò che stava per accadere? E come può la letteratura, anche quella d’evasione, aiutare a capire il mondo?

I segnali di ciò che sta accadendo ci sono stati, eccome, e la gente ci ha avvertito, sia sui giornali, sia sui libri, sia sulle pagine dei gruppi di esperti, ecc. Ma i loro avvertimenti non sono stati ascoltati. Penso che la letteratura possa aiutare a diffondere la notizia a un maggior numero di persone, ma il problema è che, poiché la storia è fittizia, la gente potrebbe pensare che anche i fatti spaventosi siano inventati o esagerati.

Scrivere il primo romanzo è sempre complicato, ma anche emozionante. Si scrive con la leggerezza di non avere ancora un contratto e delle scadenze da rispettare e l’autore è ancora l’unico a poter osservare i suoi personaggi mentre prendono vita. Sei pronto a fare il passo successivo? Il successo del primo romanzo ha potuto influenzare la stesura del seguito o il senso di libertà persiste nonostante tutto?

Ero piuttosto nervoso all’idea di scrivere il secondo romanzo, perché doveva essere almeno altrettanto buono del primo, e allo stesso tempo essere sia qualcosa di più dello stesso, sia qualcosa di totalmente nuovo. Ma poiché non avevo pensato di scrivere un secondo libro quando ho scritto il primo, la scrittura ha avuto una certa gioia pionieristica.

Thriller, spy story, romanzo di denuncia sociale. Il suo libro può essere collocato in diverse categorie, grazie alla profonda stratificazione sia della trama che dei personaggi. Dal tuo punto di vista, come dovrebbe considerare il tuo romanzo il pubblico? Pensi che la definizione di thriller possa sminuirne il valore?

Purtroppo sì. E vorrei davvero che i temi del libro venissero discussi di più. Ma i thriller sono raramente presi sul serio dai media, nonostante il fatto che spesso trattino di minacce e problemi reali. Quindi, fino al giorno in cui gli editorialisti dei giornali non apriranno gli occhi sul genere, preferisco la definizione che attira il maggior numero di lettori (che immagino sia “thriller” o forse “spy-thriller”), e poi spero solo che il lettore apprezzi il fatto di ottenere qualcosa di più.

C’è una domanda che accompagna tutta la lettura: quanta verità c’è nel romanzo?

Tutti i fatti sono veri: gli agenti dormienti, i vecchi anelli di spionaggio pronti a essere attivati, i programmi Stay put e Stay behind, le bombe nascoste e il sostegno svedese alla Germania dell’Est con molti svedesi affermati come utili idioti. L’abuso sistematico della ragazza è un mix di “trappole” del KGB/Stasi e delle orribili rivelazioni su Bill Cosby negli Stati Uniti e Peter Saville nel Regno Unito.

Se dovessi scegliere tre parole che ti rappresentano, quali sarebbero?

Curioso, testardo e gentile.

Se dovessi scegliere tre cose di cui non potresti mai fare a meno, escludendo ovviamente la scrittura, quali sarebbero?

“Cose”, quindi non la mia famiglia, giusto? (A loro non piace quando li chiamo “cose”). Allora direi il mio computer, i miei libri e un ottimo paio di cuffie. (E se i “libri” non contano come una cosa, scelgo un ottimo amplificatore per cuffie).

Prima di salutarci e, meglio ancora, di inaugurare un saluto d’eccezione, quale messaggio o augurio vorresti lasciare ai nostri lettori?

Spero che leggano tutti i libri di Sara Nowak e si godano le storie – ma anche che siano consapevoli che le parti più spaventose della nostra storia e del mondo di oggi sono vere.

These days we are dealing with an international crisis that seems to have plunged the world back at least thirty years. Everyday we are talking of nuclear risk, iron curtains, espionage, all themes present in your novel, Geiger. Does this mean that history never really dies and that despite this, learning from the past is still impossible?

One central theme in Geiger and the following parts is that the cold war never ended, that there are old spies embedded in our westerns societies ready to do the russian leaders bidding, and that the men in power in Russia all are old KGB-men with the same view of the world as back then, and they are ready to wreak havoc in Europe, which has so tragically been proven since Geiger was published. We haven’t learned from the past, but we must start doing that. The fight for democracy is never over, it’s a constant process.

It is clear the narrative choice you have adopted not to tell the world of spies in a Mission Impossible style, just to stay in touch with your work in film and television. Your novel is rather reminiscent of those great John Le Carré frescoes and the quality of the plot seems almost the result of a direct experience with that reality. Did you have access to direct testimonials?

I grew up during the cold war, in the north of Sweden, where there were lots of military zones all around and constant talk of spies and the threat of an invasion by the Soviet Union. My parents were very politically active in the far left, so our phone was tapped by the security services and my fathers employer was warned about his political engagement. My parents also had friends who were personal friends with some of the most well-known palestinian terrorists or freedom fighters (depending on your world view). It is only in the research for my books that I have realized how well they were connected, these persons i met in my childood, and that they actually went to training camps in the Middle East. On top of that I have read close to a hundred books for Geiger and listened to dozens of interviews with old activists and collaborators.

Sara Nowak is a strong woman, an uncompromising policewoman but also a fragile person, especially in her private life. She is a mother frightened by the world towards which her children are destined to go with the passage into adulthood, and she is also an insecure wife, perhaps because she is too conditioned by her profession. Do you think this is an accurate portrait of the contemporary woman?

She is more inclined to resort to violence than the average woman I think, but I definitely think she shares the worries for her children and their future with most other women today, even those who are strong and capable in other areas. Most of us want to see our kids grow up to be strong and independent, but I think a lot of parents today worry about wether they have done enough to prepare their offspring for life. The world today is so complex. And in her job Sara has seen so many of the darkest side of humanity. No wonder she is worried.

A recurring element in the book is the criticism of the male universe. Do you consider yourself a feminist? Do you think that man has failed in his role as builder of society?

If a feminist is someone who believes in equal rights for men and women (and all non-binary), I am definitely a feminist. I find it upsetting that so much trafficking and domestic violence goes unpunished. And it just goes on and on. In effect, our societies don’t care about all those tragedies and ruined lives, and I think the reason to a big extent is that the judicial systems are dominated by middleaged and older conservative men.

A central theme of the novel is the geopolitical location of Sweden, almost a sort of crossroads of the international plots hatched by the superpowers, the same ones that today seem to be heading inexorably towards a new conflict. Is this what makes your country the ideal setting for a thriller like this?

Sweden’s location and the fact that we were neutral for 200 years, at least officially, has made Sweden a great meeting ground for spies for a long time. Both during the second world war and the cold war it was a perfect place to meet, since you could get here pretty easy from different sides and meet under safe conditions. I also think that swedish naivety was a great help for those spies and conspirators. And for the same reason Sweden was a popular venue for terrorists from different parts of the world in the seventies. They came from South America, Japan, the Middle East, Italy and West Germany to meet and organize cooperation.

What impresses about Geiger is its close connection with reality, despite the fact that the book was published in Sweden two years ago (while it has just arrived in Italy). Do you think there have been signs of what was about to happen for some time now? And how can literature, even escapist literature, help to understand the world?

There have been signs of what is happening now, absolutely, and people have warned us, both in newspapers, books and homepages for think tanks etc. But their warnings haven´t been heeded. I think literature can help spread the word to more people, but a problem is that since the story is fictitious, people may think that even the scary facts are made up or exaggerated.

Writing the first novel is always complicated, but also exciting. It is written with the lightness of not yet having a contract and deadlines to respect and the author is still the only one who can observe his characters as they come to life. Are you ready to take the next step? Could the success of the first novel affect the writing of the sequel or does that sense of freedom persist despite everything?

I was pretty nervous to write the second one, since it had to be at least as good as the first one, and at the same time be both more of the same, and something totally new. But since I hadn´t thought of writing a second one when I wrote the first one, the writing had some pioneering joy to it.

Thriller, spy story, social denunciation novel. Your book can be placed in different categories, thanks to the deep layering of both the plot and the characters. From your point of view, how should the public view your novel? Do you think the definition of a thriller can diminish its value?

Unfortunately, I think it can. And I really would like the themes in the book to be discussed more. But thrillers are seldom taken seriously by media, despite the fact that they often deal with real threats and problems. So, until the day the newspaper columnists open their eyes for the genre, I prefer the definition that draws the most readers (which I guess is “thriller” or maybe “spy-thriller”), and then I just hope that the reader appreciates that they get a bit more than that.

There is a question that accompanies the whole reading: how much truth is there in the novel?

All the facts are true: about sleeper agents, old spy rings ready to be activated, about the Stay put and Stay behind programs, the hidden bombs and about Swedens support of East Germany with a lot of well established swedes as useful idiots. The systematized abuse of the young girl is a mix of the KGB/Stasi “honey traps” and the horrible revelations about Bill Cosby in the US and Peter Saville in the UK.

If you had to choose three words that represent you, what would they be?

Curious, stubborn and kind.

If you had to choose three things that you could never do without, obviously excluding writing, what would they be?

“Things”, so not my family, right? (They don´t like it when I call them “things”.) Then I would say my computer, my books and a great pair of headphones. (And if “books” doesn’t count as one thing, I choose a really good headphone amplifier.)

Before saying goodbye and even better, to inaugurate a greeting of exception, what message or wish would you like to leave to our readers?

I hope they will read all the books about Sara Nowak and enjoy the stories – but also be aware that the most scary parts about our history and the world today are true.

ThrillerLife ringrazia Gustaf Skördeman

a cura di Andrea Martina e Nina Palazzini